File Photo / Houma Courier

GRAND CAILLOU -- More than a week after a 9-foot storm surge from Hurricane Rita swept over southern Louisiana, Jimmy Sothern is still trying to dry out his cypress-log cabin. His doors are open to the sunlight and soft breeze and furniture is drying on the deck built over the bayou.

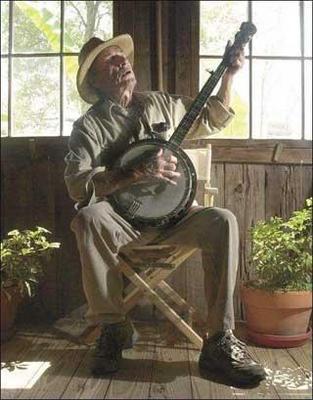

Jimmy Sothern of Grand Caillou strums his banjo.

Sothern suffered 3 feet of flooding in the cabins he built on the bayou, and his children have been helping him clean.

"There’s no air conditioning and everything has floated all around, but there’s a lot of people worse off than me," Sothern said.

Sothern is a geologist, environmentalist, historian, musician, artist and artisan. He is a cultural placeholder -- someone who holds dear the history of his people and brings it to light again and again. He does it out of love, and in part, to measure the losses.

Regardless of the topic of conversation, Sothern soon turns it back to geology: the sinking sedimentary basin that is southern Louisiana, the need to return the Mississippi River back to its wild state and the wrongs humans have brought to bear on Louisiana’s land and waterways.

Sothern said that in 1935, the U.S. Geological Survey set bronze elevation markers at intervals along the shell roads leading from Houma. Over the years, as roads were paved, the markers were covered. But Sothern found an older man who remembers one marker’s placement and elevation. Sothern said the marker stated the land was 5 feet above sea level. By 1980, that same spot had sunk 2 feet.

"The Mississippi River, before people settled along its banks and began protecting their homes with levees, deposited silt carried from upriver flooding and created deltas in the Gulf waters," Sothern said.

But the delta building no longer occurs because levees built after the 1927 flood prevent the river from changing course as it once did. Without the river depositing rich soil and land-building sediment in the coastal estuaries, south Louisiana has begun to sink.

And that means storm-driven waters will bring ever more destruction to vulnerable low-lying communities, as shown in recent weeks after hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

"We’re sitting right over the largest subsiding basin in the world," Sothern said, adding there’s a simple reason why the people of Grand Caillou, Dulac, Pointe-aux-Chenes and nearby areas continue to live in the watery realm. "I think they love it here."

Sothern moved to Grand Caillou after the death of his wife in 1977. Together the Sotherns raised six children.

Sothern has no plans to move away from the bayou, although being flooded several times in the past few years has caused him to consider it. His eyes light up when remembering the friendly people and wooded mountains of North Carolina, where friends welcomed him during the last hurricane, and where he played the banjo with a bluegrass band.

But moving to North Carolina would mean leaving the home he built with his own hands. As he has done with every new endeavor, Sothern researched authentic Acadian culture before building and learned that traditional cabins are built with certain elements. Their design makes for a graceful harmony with nature: higher ceilings allow the summer heat to rise, and the cooling evening shade falls around the south or easterly positioned wide front porches. Rainwater sluices easily off of pitched roofs. The three cabins along Sothern’s acre of land are marked with a sign that reads simply "Bayou Cabins." There is the cabin that Sothern lives in, the old-style bar and dance hall that he reserves for private use, and the demonstration cabin built as a model. Sothern has stopped building cabins because he now has to raise them high above the flood line.

Sothern is home on the bayou after several days cooking for evacuees at the Houma-Terrebonne Civic Center, where his son is the executive chef. The Civic Center is serving as a temporary home for Hurricane Katrina evacuees from New Orleans, and a shelter for area families that fled Rita’s flooding.

He is visibly moved when recounting the generosity shown Louisiana residents by people from around the world. "You can’t put a value on that because of the love that came with it," Sothern said, and is for a moment, uncharacteristically quiet.

In his kaleidoscopic childhood, Sothern attended 21 schools in 11 years. His Texas father was an oil driller by trade; his Louisiana mother raised the children. As soon as one well was struck, the family moved on to the next Gulf Coast oil town. The transitory life was hard on Sothern, but he learned to adapt to abrupt changes in culture.

"In Texas, the kids made fun of my Cajun accent, and back in Louisiana they said I talked like an uppity Texan," Sothern said. "But Cajun people are really marvelous. If you make fun of them, they’ll laugh with you."

His favorite memories are of living with his grandparents on the grounds of Southdown Plantation. "That was the most stable time," Sothern said. "Those are some of the happiest days of my life."

Sothern stays in touch with friends from that time, and has two expertly rendered pen-and-ink drawings to remind him of those days: one of the cabins at Southdown, and another of La Trouvaille, a restaurant in Chauvin where Sothern played Cajun music on Saturday nights.

"I fell in love with Houma from the very first minute," he said.

He remembers fondly a Terrebonne Parish of earlier times, when Houma was mainly accessible by water, and families went to town on trawl boats.

"Oyster boats would come in loaded, and I would hear oyster shuckers and shrimp peelers going to work at dawn," Sothern said. "The Courthouse Square was a popular meeting place. Benches were always full and people stopped to visit with one another."

Sothern likened Houma’s downtown in the late 1930s to New Orleans’ French Quarter, bustling with shops, bars and cafes.

"During World War II, Saturday nights looked like a foreign city, like Shanghai," he said. "There were so many people from other parts of the world."

Not content to keep a lifetime of knowledge -- much of it self-acquired -- to himself, Sothern has published three books and taught science courses at Louisiana State University and at L.E. Fletcher Technical Community College in Houma.

He’s led Cajun culture tours and taught himself to sing old-time Cajun songs in French, as well as popular ballads.

His passion for the culture and people of Louisiana burns as brightly as ever, even as he worries about its eventual extinction.

"Cajun culture is disappearing," Sothern said. "The only thing holding it together is Cajun music."

His dream for south Louisiana and the culture that makes it unique is simple: "My beloved homeland, as a safe place to keep on catching oysters, shrimp, redfish and trout, for our great-great-great-grandchildren," Sothern said. "Wherever our final journey ends -- I hope we’re catching trout."

-- Jan Clifford / The Houma Courier